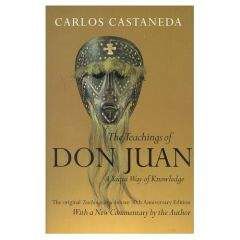

Карлос Кастанеда - Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки

Скачивание начинается... Если скачивание не началось автоматически, пожалуйста нажмите на эту ссылку.

Жалоба

Напишите нам, и мы в срочном порядке примем меры.

Описание книги "Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки"

Описание и краткое содержание "Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки" читать бесплатно онлайн.

Carlos Castaneda, under the tutelage of don Juan, takes us through that moment of twilight, through that crack in the universe between daylight and dark into a world not merely other than our own, but of an entirely different order of reality. Anthropology has taught us that the world is differently defined in different places. Don Juan has shown us glimpses of the world of a Yaqui sorcerer and Castaneda presents it in such a way that enables us to apprehend it with a reality that is utterly different from our own. This is the special virtue of this work. Castaneda asserts that this world has its own inner logic. He explains it from inside, as it were — from within his own rich and intensely personal experiences while under don Juan’s tutelage — rather than to examine it in terms of our logic. Through this experience, Castaneda leads us to understand that our own world is a cultural construct and from the perception of other worlds, we see our own for what it is.

Don Juan pointed out that in the world of everyday life, human beings make use of intent and intending in the manner in which they interpret the world. Don Juan, for instance, alerted me to the fact that my daily world was not ruled by my perception, but by the interpretation of my perception. He gave as an example the concept of university, which at that time was a concept of supreme importance to me. He said that university was not something I could perceive with my senses, because neither my sight nor my hearing, nor my sense of taste, nor my tactile or olfactory senses, gave me any clue about university. University happened only in my intending, and in order to construct it there, I had to make use of everything I knew as a civilized person, in a conscious or subliminal way.

The energetic fact of the universe being composed of luminous filaments gave rise to the shamans' conclusion that each of those filaments that extend themselves infinitely is a field of energy. They observed that luminous filaments, or rather fields of energy of such a nature converge on and go through the assemblage point. Since the size of the assemblage point was determined to be equivalent to that of a modern tennis ball, only a finite number of energy fields, numbering, nevertheless, in the zillions, converge on and go through that spot.

When the sorcerers of ancient Mexico saw the assemblage point, they discovered the energetic fact that the impact of the energy fields going through the assemblage point was transformed into sensory data; data which were then interpreted into the cognition of the world of everyday life. Those shamans accounted for the homogeneity of cognition among human beings by the fact that the assemblage point for the entire human race is located at the same place on the energetic luminous spheres that we are: at the height of the shoulder blades, an arm's length behind them, against the boundary of the luminous ball.

Their seeing—observations of the assemblage point led the sorcerers of ancient Mexico to discover that the assemblage point shifted position under conditions of normal sleep, or extreme fatigue, or disease, or the ingestion of psychotropic plants. Those sorcerers saw that when the assemblage point was at a new position, a different bundle of energy fields went through it, forcing the assemblage point to turn those energy fields into sensory data, and interpret them, giving as a result a veritable new world to perceive. Those shamans maintained that each new world that comes about in such a fashion is an all-inclusive world, different from the world of everyday life, but utterly similar to it in the fact that one could live and die in it.

For shamans like don Juan Matus, the most important exercise of intending entails the volitional movement of the assemblage point to reach predetermined spots in the total conglomerate of fields of energy that make up a human being, meaning that through thousands of years of probing, the sorcerers of don Juan's lineage found out that there are key positions within the total luminous ball that a human being is where the assemblage point can be located and where the resulting bombardment of energy fields on it can produce a totally veritable new world. Don Juan assured me that it was an energetic fact that the possibility of journeying to any of those worlds, or to all of them, is the heritage of every human being. He said that those worlds were there for the asking, as questions are sometimes begging to be asked, and that all that a sorcerer or a human being needed to reach them was to intend the movement of the assemblage point.

Another issue related to intent, but transposed to the level of universal intending, was, for the shamans of ancient Mexico the energetic fact that we are continually pushed and pulled and tested by the universe itself. It was for them an energetic fact that the universe in general is predatorial to the maximum, but not predatorial in the sense in which we understand the term: the act of plundering or stealing, or injuring or exploiting others for one's own gain. For the shamans of ancient Mexico, the predatory condition of the universe meant that the intending of the universe is to be continually testing awareness. They saw that the universe creates zillions of organic beings and zillions of inorganic beings. By exerting pressure on all of them, the universe forces them to enhance their awareness, and in this fashion, the universe attempts to become aware of itself. In the cognitive world of shamans, therefore, awareness is the final issue.

Don Juan Matus and the shamans of his lineage regarded awareness as the act of being deliberately conscious of all the perceptual possibilities of man, not merely the perceptual possibilities dictated by any given culture whose role seems to be that of restricting the perceptual capacity of its members. Don Juan maintained that to release, or set free, the total perceiving capacity of human beings would not in any way interfere with their functional behavior. In fact, functional behavior would become an extraordinary issue, for it would acquire a new value. Function in these circumstances becomes a most demanding necessity. Free from idealities and pseudo-goals, man has only function as his guiding force. Shamans call this impeccability. For them, to be impeccable means to do one's utmost best, and a bit more. They derived function from seeing energy directly as it flows in the universe. If energy flows in a certain way, to follow the flow of energy is, for them, being functional. Function is, therefore, the common denominator by means of which shamans face the energetic facts of their cognitive world.

The exercise of all the units of the sorcerers' cognition allowed don Juan and all the shamans of his lineage to arrive at odd energetic conclusions which at first sight appear to be pertinent only to them and their personal circumstances, but which, if they are examined with care, may be applicable to any one of us. According to don Juan, the culmination of the shamans' quest is something he considered to be the ultimate energetic fact, not only for sorcerers, but for every human being on Earth. He called it the definitive journey.

The definitive journey is the possibility that individual awareness, enhanced to the limit by the individual's adherence to the shamans' cognition, could be maintained beyond the point at which the organism is capable of functioning as a cohesive unit, that is to say, beyond death. This transcendental awareness was understood by the shamans of ancient Mexico as the possibility for the awareness of human beings to go beyond everything that is known, and arrive, in this manner, at the level of energy that flows in the universe. Shamans like don Juan Matus defined their quest as the quest of becoming, in the end, an inorganic being, meaning energy aware of itself, acting as a cohesive unit, but without an organism. They called this aspect of their cognition total freedom, a state in which awareness exists, free from the impositions of socialization and syntax.

These are the general conclusions that have been drawn from my immersion in the cognition of the shamans of ancient Mexico. Years after the publication of The Teachings of Don Juan: A Yaqui Way of Knowledge, I realized that what don Juan Matus had offered me was a total cognitive revolution. I have tried, in my subsequent works, to give an idea of the procedures to effectuate this cognitive revolution. In view of the fact that don Juan was acquainting me with a live world, the processes of change in such a live world never cease. Conclusions, therefore, are only mnemonic devices, or operational structures, which serve the function of springboards into new horizons of cognition.

ВВЕДЕНИЕ

Летом 1960 года, будучи студентом антропологии Калифорнийского университета, что в Лос-Анджелесе, я совершил несколько поездок на юго-запад, чтобы собрать сведения о лекарственных растениях, используемых индейцами тех мест. События, о которых я описываю здесь, начались во время одной из поездок.

Ожидая автобуса в пограничном городке, я разговаривал со своим другом, который был моим гидом и помощником в моих исследованиях. Внезапно наклонившись, он указал мне на седовласого старого индейца, сидевшего под окошком, который, по его словам, разбирался в растениях, особенно в пейоте. Я попросил приятеля представить меня этому человеку.

Мой друг подошел к нему и поздоровался. Поговорив с ним немного, друг жестом подозвал меня и тотчас отошел, не позаботившись о том, чтобы нас познакомить… Старик ни в коей мере не был удивлен. Я представился, а он сказал, что его зовут Хуан и что он к моим услугам. По моей инициативе мы пожали друг другу руки и немного помолчали. Это было не натянутое молчание, но спокойствие естественное и ненапряженное с обеих сторон.

Хотя его темное лицо и морщинистая шея указывали на возраст, меня поразило, что его тело было крепкое и мускулистое… Я сказал ему, что интересуюсь лекарственными растениями. Хотя, по правде сказать, я почти совсем ничего не знал о пейоте, я претендовал на то, что знаю очень много и даже намекнул, что ему будет очень полезно поговорить со мной.

Когда я болтал в таком духе, он медленно кивнул и посмотрел на меня, но ничего не сказал. Я отвел глаза от него, и мы кончили тем, что сидели друг против друга в гробовом молчании. Наконец, как мне показалось, после очень долгого времени, дон Хуан поднялся и выглянул в окно. Как раз подходил его автобус. Он попрощался и покинул станцию.

Я был раздражен тем, что говорил ему чепуху и тем, что он видел меня насквозь.

Когда мой друг вернулся, он попытался утешить меня в моей неудаче… Он объяснил, что старик часто бывает молчалив и необщителен — и все-таки я долго не мог успокоиться.

Я постарался узнать, где живет дон Хуан, и потом несколько раз навестил его. При каждом визите я пытался спровоцировать его на обсуждение пейота, но безуспешно… Мы стали, тем не менее, очень хорошими друзьями, и мои научные исследования были забыты или, по крайней мере, перенаправлены в русло весьма далекое от моих первоначальных намерений.

Друг, который представил меня дону Хуану, рассказал позднее, что старик не был уроженцем Аризоны, где мы с ним встретились, но был индейцем племени Яки из штата Сонора в Мексике.

Сначала я видел в доне Хуане просто довольно интересного человека, который много знал о пейоте и который замечательно хорошо говорил по-испански. Но люди, с которыми он жил, верили, что он владеет каким-то «секретным знанием», что он был «брухо». Испанское слово «брухо» означает одновременно врача, колдуна, мага. Оно обозначает человека, владеющего необыкновенными и, чаще всего, злыми силами.

Я был знаком с доном Хуаном целый год, прежде чем вошел к нему в доверие. Однажды он рассказал, что имеет некоторые знания, которые он получил от учителя, благодетеля, как он его называл, который направлял его в, своего рода, ученичестве. Дон Хуан, в свою очередь, взял меня в свои ученики, но предупредил, что мне нужно принять твердое решение, ибо обучение будет долгим и утомительным.

Рассказывая о своем учителе, дон Хуан использовал слово «диаблеро» (по-испански диабло — дьявол, черт), позднее я узнал, что диаблеро — термин, используемый только соноракскими индейцами. Он относится к злому человеку, который практикует черную магию и способен превращаться в животных — птицу, собаку, койота или любое другое существо.

Во время одной из поездок в Сонору, со мной произошел любопытный случай, хорошо иллюстрирующий чувства индейцев к диаблеро… Как-то ночью я ехал с двумя испанскими друзьями, когда я увидел крупную собаку, пересекшую дорогу. Один из моих друзей сказал, что это была не собака, а гигантский койот. Я притормозил и подъехал к краю дороги, чтобы получше разглядеть животное. Постояв несколько секунд в свете фар, оно скрылось в чапарале.

Подписывайтесь на наши страницы в социальных сетях.

Будьте в курсе последних книжных новинок, комментируйте, обсуждайте. Мы ждём Вас!

Похожие книги на "Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки"

Книги похожие на "Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки" читать онлайн или скачать бесплатно полные версии.

Мы рекомендуем Вам зарегистрироваться либо войти на сайт под своим именем.

Отзывы о "Карлос Кастанеда - Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки"

Отзывы читателей о книге "Учения дона Хуана: Знание индейцев Яки", комментарии и мнения людей о произведении.